Clinical Exercise: Lower Extremity Fasciotomy

Scenario:

A patient was admitted with a mid-thigh injury to the superficial femoral artery, which was repaired surgically with a femoral vessel exposure and control. The patient awakens post-surgery, and after several hours begins to describe considerable pain when moving their foot and toes. On physical examination you find sensation of the dorsum of the foot is diminished on the injured side, the dorsal pulse is weak to absent, and the musculature of the leg feels hard/tense to palpation.

Diagnosis:

These symptoms are classical signs of compartment syndrome of the leg in which excessive pressure builds up in a fascial compartment.

The diagnosis of an extremity compartment syndrome is entirely clinical following the Five P's; Pain (pain out of proportion to the movement), Pulselessness (loss of distal pulse), Pallor/poikiothermia (cool and pale skin), Paralysis (inability to operate the muscles), and Paresthesia (numb feeling). The limb can also feel tense/hard to palpation due to the pressure within the compartments.

If physical examination is unreliable (e.g. if the patient was unconscious and unable to relate pain/parethesia/paralysis information) the pressure of the compartment can be measured directly with a pressure sensor (i.e. a Stryker needle apparatus). Rarely would imaging be needed to make a diagnosis.

Mechanism:

In this case the compartment syndrome has arisen as a sequelae (consequence) of the patient's mid-thigh arterial injury. Burns, blunt force trauma, fractures, vascular injury, and muscle overuse in athletes are common precursors to the development of compartment syndrome.

Since the crural fascia is essentially inelastic, interstitial pressure within the compartment has nowhere to expand. If the pressure within the compartment exceeds that of the arterial blood pressure entering the compartment, then the contents of the compartment can become ischemic.

Untreated this leads to necrosis (death) of the muscle tissue and a likely need to amputate the limb at that point. If not amputated, breakdown products of the necrotic muscle tissue enter the blood supply and cause kidney stress/failure (rhabdomyolysis) that can lead to death. Typically, the window of time in which to treat without these serious sequelae is 3-5 hours.

The early treatment involves performing a fasciotomy, a procedure in which the skin and fascia are slit open allowing the muscle tissue to bulge out relieving the pressure. Due to the serious consequences of not treating a compartment syndrome, there is a low threshold for taking action and a fasciotomy may be performed prophylactically in cases where specific clinical criteria are met.

Treatment (perform these steps on the donor in a mock-procedure):

PREPARATION: Send a member of your team to the instrument supply tables to fetch a purple skin surgical marker. Perform the procedure on both legs as the skin/fascia incisions in this procedure open the compartments so that we can examine their contents after this procedure is complete.

The procedure for this trauma scenario, which is likely affecting the entire leg, would be a two-incision, four-compartment fasciotomy. We will be performing only the lateral incision to decompress the anterior and lateral compartments. A surgeon would also perform a medial incision to decompress the superficial posterior and deep posterior compartments. However, since we have already dissected the posterior leg we will not be performing that half of the procedure.

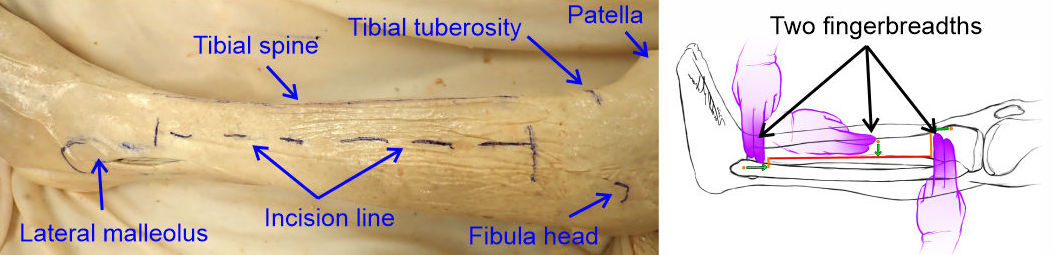

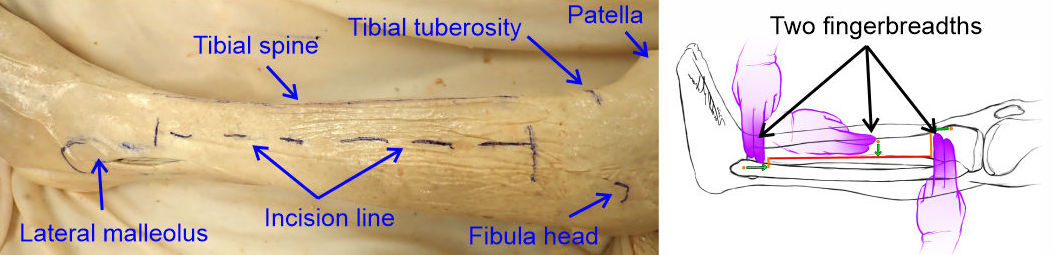

1) Mark the skin over the bony landmarks of the lateral malleolus (previously marked), the tibial tuberosity (bump on the tibia just inferior to the patella where the patellar tendon inserts), and the spine of the tibia (lateral edge of the tibia, aka 'shin bone').

The head of the fibula is another commonly used landmark, however this can be difficult to palpate in an individual with larger body habitus (i.e. body shape/composition) as well as tissue rigidity due to the compartment syndrome (or in our case due to the embalming).

2) Mark the planned incision, which will go from two fingerbreadths proximal to the lateral malleolus, two fingerbreadths distal to the tibial tuberosity, following two fingerbreadths posterolateral to the tibial spine.

3) Make an incision through the skin the full length of the incision line and with blunt dissection spread the skin widely exposing the crural fascia.

If the skin is particularly thin you may inadvertently slice into the crural fascia while making the skin incision. This can happen in the operating room as well and typically does not cause any significant problems since the crural fascia is to be incised as part of the procedure.

4) Hold the incision open with Weitlaner retractors and make a shallow tangential incision through the crural fascia from anterior to posterior across the intermuscular septum separating the anterior and lateral compartments.

Avoid cutting too deeply as muscle tissue is immediately deep to the crural fascia (less than a millimeter). The goal is to cut the crural fascia without causing excessive damage to the underlying muscle tissue.

The intermuscular septum often shows as a thin white line just anterior to the axis of the fibular bone (malleolus to fibular head). The septum is not always apparent as a line in all individuals and the broader pale bands of underlying muscle tendons can be confused as the septum. As a secondary method, several small perforating vessels emerge along the intermuscular septum into the subcutaneous tissue and their presence is indicative of the position of the septum. If the cut correctly spans across the septum, you can also grasp the sheet of septal fascia easily with the end of forceps at the cut point.

This is classically called a "H incision" as the final set of fascial incisions at the end of the procedure will resemble an elongated H shape. This tangential incision forms the horizontal part of the H shape final pattern.

5) Work the closed tips of scissors under the crural fascia over the anterior compartment to expand the space (i.e. 'tunnel' under the crural fascia to make room for cutting the fascia) and then use partly open scissors to slit the crural fascia over the anterior compartment parallel to the intermuscular septum, distally from the H incision to 2 fingerbreadths from the lateral malleolus.

In most cases the crural fascia parts easily when pushing partly open scissors in a process similar to cutting cloth or paper with partly open scissors. Avoid pushing the scissor tips into the underlying muscle tissue as that can cause additional injury by slitting muscle tissue.

6) Repeat the tunneling with closed scissors and slitting with partly open scissors to open the crural fascia over the anterior compartment parallel to the intermuscular septum proximally from the H incision to 2 fingerbreadths from the tibial tuberosity.

These two incisions form one arm of the H pattern and fully open the anterior compartment.

7) Repeat the above steps with the lateral compartment (tunneling then slitting crural fascia proximally and distally) to fully open the crural fascia over the lateral compartment

This completes the H-shaped pattern with the longitudinal incisions forming the arms of the letter H decompressing both the anterior and lateral compartments.

Outcome:

The incisions in the crural fascia allow the muscles to bulge out relieving the pressure and restoring adequate blood flow to the tissues. The skin incision is left open and covered lightly with sterile dressings. Over the next few days the patient returns several times to the operating room to progressively close the skin incision as the swelling of the musculature of the leg subsides. The slits in the crural fascia will knit together with time and are usually not sutured. Following physical therapy the patient makes a full recovery.